Half of the world’s 100 largest cities are experiencing high levels of water stress, with 38 located in regions classified as facing “extremely high water stress,” according to new analysis and mapping.

Water stress occurs when demand for water for public supply and industrial use approaches or exceeds available resources, often due to poor water management compounded by the impacts of climate change.

Joint analysis by Watershed Investigations and The Guardian mapped major cities against stressed river catchments, identifying Beijing, Delhi, Los Angeles, New York and Rio de Janeiro as among the most severely affected. London, Bangkok and Jakarta were also found to be in highly stressed regions.

Separate research using Nasa satellite data, conducted by scientists at University College London (UCL), examined long-term trends in water availability across the same cities. The data shows that cities such as Chennai, Tehran and Zhengzhou have experienced significant drying over the past two decades, while others including Tokyo, Lagos and Kampala have become markedly wetter. These trends are presented in a new interactive global water security atlas.

Approximately 1.1 billion people live in large urban areas situated in regions undergoing long-term drying, compared with about 96 million living in cities located in areas showing strong wetting trends. Researchers caution, however, that satellite data does not capture local-scale factors influencing water access.

Cities experiencing increased rainfall are largely concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, with Tokyo and Santo Domingo as notable exceptions. In contrast, many of the cities facing the strongest drying signals are located across Asia, particularly in northern India and Pakistan.

Tehran, now entering its sixth consecutive year of drought, is approaching a potential “day zero” scenario, when water supplies could be exhausted. Iran’s president, Masoud Pezeshkian, warned last year that the city could face evacuation if conditions do not improve. Other cities, including Cape Town and Chennai, have previously neared similar crises, while several fast-growing urban centres are located in regions vulnerable to future water shortages.

Professor Mohammad Shamsudduha, a water crisis and risk reduction expert at UCL, said Nasa’s Grace satellite mission provides critical insight by tracking changes in water storage globally, offering early warnings of emerging water insecurity.

The findings come as the United Nations declared this week that the world has entered a state of “water bankruptcy,” where damage to some water resources has become permanent and irreversible. Professor Kaveh Madani, director of the United Nations University Institute for Water Environment and Health, said mismanagement is often the primary driver of water crises, with climate change worsening existing problems rather than causing them outright.

The World Bank Group has also raised concerns, reporting that global freshwater reserves have declined sharply over the past two decades. The planet is losing an estimated 324 billion cubic metres of freshwater annually, enough to supply 280 million people each year, affecting major river basins worldwide.

In England, the Environment Agency warns that an additional five billion litres of water per day may be required by 2055 to meet public supply needs, with agriculture and energy sectors potentially requiring an extra one billion litres daily. While groundwater could offer a more climate-resilient option, experts caution that insufficient monitoring and management pose serious risks.

Recent water outages in parts of southern England have highlighted infrastructure vulnerabilities. In response, the UK government has published a new water white paper proposing reforms including stricter infrastructure checks, expanded regulatory powers and the creation of a chief water engineer role.

Home

Uncategorized

Half of the World’s 100 Largest Cities Face Severe Water Stress, Analysis Reveals

Uncategorized Half of the World’s 100 Largest Cities Face Severe Water Stress, Analysis Reveals

Share

Latest Posts

Related Articles

Uncategorized

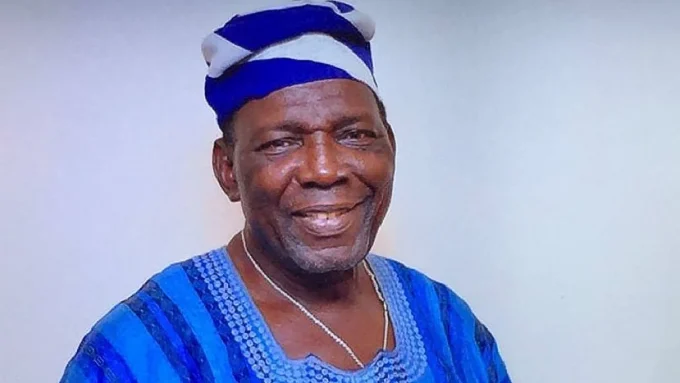

Life and Times of Nigeria’s First Indigenous Coach, Adegboye Onigbinde

The death of veteran football tactician, High Chief Adegboye Onigbinde, has cast...

19 hours Ago

Uncategorized

Gunmen Abduct Ondo Council Official, Two Others Near Akure Airport

Gunmen suspected to be kidnappers have abducted the Secretary of Okeluju Local...

1 day Ago

Uncategorized

Bwala: Al Jazeera Did Not Inform Me My Past Statements Would Be Questioned

Special Adviser to the President on Media and Policy Communication, Daniel Bwala,...

2 days Ago

Uncategorized

Explosion Rocks U.S. Embassy in Oslo Amid Rising Middle East Tensions

An explosion struck the United States Embassy in Oslo, Norway, in the...

2 days Ago

Leave a comment